G-8 Summit - TheStar.com Special SeriesTheStar.com - The Series

Jun. 25, 2005. 01:00 AMIn the lead up to the G-8 Summit in Gleneagles, Scotland, July 6-8, the Star dispatched journalists to Africa, India, China and the Arctic. The series focuses on the challenges the G-8 has pledged to make progress on: HIV/AIDS, poverty and global climate change.

- Introduction: Will Tony Blair's summit make a difference?

- Swaziland: A tiny African kingdom tries to tackle the Goliath of epidemics.

- South Africa: Prevention and treatment gain traction against HIV/AIDS

- India could be the new epicentre in a disaster of global proportions.

- In the Arctic, the signals are loud and clear. But is anyone listening?

- China's colossal economic engines drive the economy, but clog the air.

- Climate change isn't just global. It's local. What you can do in the GTA.

Averting disaster

Jun. 25, 2005. 08:17 AM

OAKLAND ROSS

FEATURE WRITER

JOHANNESBURG—A Swedish diplomat by the name of Bernt Carlsson was musing about the parlous state of this fragile blue orb.

At the time, Carlsson was the United Nations Commissioner for Namibia, and he happened to find himself one morning in a rather gloomy lounge at the international airport in the Angolan capital of Luanda, a largely gutted city, where he was chatting with a couple of foreign journalists.

The Cold War was just then ending, the Berlin Wall was being torn down, and Carlsson opined that the driving force behind those seismic geopolitical changes was a new awareness that the old world order had to change, if only because our frail and disputatious species faced an even more implacable enemy on an even deadlier battleground.

The foe, of course, was humankind itself. And the battleground was the natural environment, which was — and is — being despoiled at an enormous rate.

World leaders, said Carlsson, were finally recognizing that it was time to put ideological differences aside in order to salvage the planet and preserve our place upon it.

Maybe the urbane, soft-spoken Swede was right or maybe he was wrong. In either case, it's a parlous world, and a fragile existence.

Not long after that brief conversation in an African airport, Carlsson was among the passengers aboard Pan American Airlines Flight 103 when it exploded over Lockerbie, Scotland, in December 1988 — the target of Libyan terrorists, with the loss of all on board.

Now, 17 years later, Scotland, Africa and the imperilled state of the global environment are again in the news, as the leaders of the world's eight most powerful industrial nations prepare to gather for their annual summit.

This year, Britain will host the gathering, which will take place July 6-8 in the Scottish resort town of Gleneagles, outside Edinburgh.

These meetings are visited upon the planet every year, and they often have a largely ritualistic air — eight men and their aides dining extravagantly behind closed doors, to no great purpose, while a grab bag of protest groups play cat and mouse with heavily armed riot police somewhere outside, as tear gas fumes swirl all around.

But this year's G-8 summit — bringing together the leaders of Britain, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia and the United States — promises to be different.

Maybe only a little bit different or maybe a lot.

"Maybe `watershed' is not the right word," says Roy Culpeper, president of the North-South Institute, an Ottawa-based think tank on relations between the world's rich and its poor. "But a lot of positive things could happen."

Thank British Prime Minister Tony Blair for that. He has strived mightily during long months to make this year's edition of the annual get-together something more than a chance for a few middle-aged white men to sit down, sip single-malt whiskey, smooch cigars, and discuss exchange rates.

At the top of the agenda next month are two themes that ought to resonate deeply with everyone on this planet, whether rich, poor or in-between.

When they gather in Scotland next month, the leaders of the G-8 will be talking about global climate change and they will be talking about Africa.

And they will not be alone. Also invited this time around are the leaders of Brazil, China, India and South Africa.

Meanwhile, among those unlikely to be invited to the summit, expectations of the event are predictably mixed.

"We know it's a talk shop," says John Stremlau, head of the department of international relations at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. "Let's not get our hopes too high."

That said, lofty hopes are probably inevitable, especially given the fanfare, hoopla and spectacle that already have attached themselves to this year's gathering, to a degree that easily outstrips any that has gone before.

A panoply of international pop stars — many of them male, white and middle-aged — have organized a constellation of rock concerts in various parts of the world to accompany, or compete with, the deliberations at Gleneagles. The concerts will highlight the urgency of the issues at stake, particularly the plight of sub-Saharan Africa, a region beset by poverty, hunger and the grim spectre of AIDS.

"I think something will come out of Gleneagles," says Culpeper. "God knows, Tony Blair has been breaking both legs trying to get something out of the Americans."

Possibly the most urgent item on the agenda has to do with AIDS and its predations in much of Africa, where the disease remains a wholesale killer.

"There is absolutely no precedent for what is happening there," says Stephen Lewis, the Canadian who serves as U.N. special envoy for AIDS in Africa, "and we are nowhere near containing it."

In North America, thanks to the development of anti-retroviral medication, AIDS has been reduced from a death sentence to a chronic but manageable condition.

'It is a doomsday scenario. It's desolation. It's out of control. If we haven't made a breakthrough (on AIDS treatment) by the end of 2006, if we can't see it by that time, some countries will be struggling for survival.'

In Africa, however, where the incurable malady has already claimed a toll of victims equivalent to more than half the population of Canada, AIDS is still on the rampage and continues to devour individual lives, destroy families, and cripple whole communities with an ease and persistence that seem little short of diabolical.

In time, in its African incarnation, AIDS may cause entire countries to collapse.

"It's a dire situation," says Culpeper. "When you have the core of the labour force wiped out, then who's producing the goods?"

The question is rhetorical, because the answer — if there is one — is already buried under the good red African earth, and still the funerals continue at an alarming rate.

Even without AIDS, this continent would have its misfortunes and its woes, and yet Africa has made many impressive strides in its three or four decades of political independence, mainly in the area of education — training men and women to master the myriad technical and managerial skills required to run modern states.

Now many of these very people are among the dying or the dead, with no one to replace them. Two generations of post-colonial accomplishment must now be written off, along with the names of the deceased.

Meanwhile, the virus continues to infect, spread and kill.

True, tens of thousands of Africans are at last receiving anti-retroviral treatment, thanks to combined local and international efforts and to dramatic reductions in the drugs' once unaffordable price tags, but many millions of desperate men, women, children remain caught between the tropical heat and the pharmaceutical cold, where death is just one opportunistic infection away.

Large-scale ARV treatment programs in Africa began very late, and they have been slow to expand.

"Clearly, we have not been `in time,'" says Mark Dybul, deputy global AIDS co-ordinator at the U.S. State Department. "It has been a somewhat slow ramp-up."

Others use stronger language.

"It is a doomsday scenario," says Lewis. "It's desolation. It's out of control. If we haven't made a breakthrough (on AIDS treatment) by the end of 2006, if we can't see it by that time, some countries will be struggling for survival."

Millions of Africans already are.

It is not AIDS alone that is devastating many parts of this region, but a lethal brew of AIDS, other diseases, hunger, and an inability of overburdened and cash-strapped governments to respond to the crisis.

"The combination of food shortages and AIDS is what's killing everyone," says Lewis.

Two weeks ago, while meeting in London, the G-8 foreign ministers hammered together a precedent-setting agreement to forgive approximately $40 billion (U.S.) in debt owed to multilateral lending institutions by 15 highly indebted developing countries, most of them in Africa.

Not everyone praises the agreement. For example, Nicky Oppenheimer, a South African and chairman of De Beers International Institute for Strategic Studies in London, quickly branded the deal "a handout," when what Africa needs is "a hand up," especially through improved terms of trade with the industrialized world.

Improved terms of trade would certainly be welcome, and they will be discussed at Gleneagles, along with dramatic increases in foreign-aid spending by donor nations, but most observers are lauding the debt-relief arrangement as a good start along the way to easing Africa's overwhelming financial troubles.

But it is only a start.

"It's time for the donors to put the money where the mouths are, " says Stremlau. "We are not talking about handouts."

We are talking about people dying, not only tomorrow or next month but today.

In fact, a scant 24 hours before the G-8 ministers were putting their gold-nibbed pens to the new pact on debt relief in London, a senior official of the World Food Program was in his office in Johannesburg, typing out a desperate appeal for international help, as the ranks of the hungry in six southern Africa countries continue to escalate dramatically.

Blame AIDS. Blame another poor harvest. Both play a role, and the result is stark: there is not nearly enough food available to keep millions of people alive, much less healthy.

"Without new commitments of either cash or in-kind food resources, WFP will be unable to meet the food needs of several million highly vulnerable southern Africans," wrote Mike Sackett, the WFP's Johannesburg regional director, in a letter dated June 10. "Lives are unquestionably at stake."

This is by no means his first such plea.

'The combination of food shortages and AIDS is what's killing

everyone.' - Stephen Lewis, U.N. special envoy for AIDS in Africa

"The WFP makes these appeals," says Lewis, "and they always fall short."

And so people go hungry, and they die, for it is indeed a parlous world.

In part, you could blame the weather.

This year in southern Africa, the rains were spotty, the cornfields baked in the scorching sun and the cobs died on wilting stalks in what was the fifth consecutive year of low rainfall in the region. Granted, five years are not a long time in the grand scheme, but some here are beginning to wonder whether the term "drought" properly describes what is happening in the southern reaches of Africa and perhaps elsewhere on the continent.

"This year's rains were close to last year's, but well below 30 years ago," says Abdoulaye Balde, the World Food Program country representative in Swaziland on South Africa's eastern border. "Maybe we have a different cycle of rain than 30 years ago. We keep saying `drought,' but is it? Or are these the new norms?"

Balde does not actually use the term "climate change," but it's what he means.

For his part, Stuart Piketh, of the Climatology Action Group in Johannesburg, is reluctant to make too much of this five-year succession of parched weather.

"Drought is not uncommon to the southern African region," he says. "I'd be skeptical of saying the drought we are seeing is a climate-change signal."

This is not to say, when he gazes out at the southern African high veld and beyond, that Piketh does not observe any climate-change signals at all. In fact, he sees plenty, and they mostly take the form of "extreme weather events" — events that are becoming increasingly common, increasingly destructive and increasingly worrisome.

After all, it is nowhere written that humankind must endure forever. More than 70,000 years ago, the species was very nearly wiped out in the volcanic winter that followed a fiery eruption in Sumatra. DNA evidence suggests that we are all descended from the few thousand human survivors of that catastrophe.

Endure forever? How? In two billion years or so, the sun will explode and burn the planet Earth to a memory that no one will survive to recall.

Two years ago, writing in the February 2003 issue of Harper's magazine, American essayist Tom Bissell observed that global warming or climate change "is well under way." He labelled those who believe otherwise as "the meteorological equivalent of creationists."

In some parts of the world, of course, creationists continue to abound. Washington, D.C., is such a place, and the United States is one of two industrialized powers that have refused to ratify the Kyoto Protocol to reduce greenhouse gases. Australia is the other.

The failure of the George W. Bush administration in Washington even to treat the matter seriously is a source of profound frustration to scientists, environmentalists and no doubt many political leaders in other countries, possibly including the prime minister of a certain scepter'd isle off the west coast of Europe.

This past February, Moscow finally joined the Kyoto accord, but the whole world knows that the initiative has no hope of achieving its goals without U.S. participation.

"The U.S.A. is the biggest emitter by far," says Neil Bird, a Canadian climate-change expert currently working in Austria.

Even countries that do subscribe to Kyoto are in many cases failing to meet their obligations under the accord. According to Bird, such countries include Canada, as well as Austria, Belgium, Italy, Japan, Spain and Switzerland. Germany is slightly over target as well.

Meanwhile, the world's two most populous countries, China and India, are both industrializing at a frantic pace, which is good news for anti-poverty advocates. It means the planet will almost certainly reach the U.N.'s goal of cutting the ranks of the world's poor in half by 2015.

On the other hand, the rapid economic ascents being engineered by Beijing and Delhi also spell grim tidings for the global campaign to limit greenhouse emissions.

Piketh, for one, is not optimistic that much will be accomplished at Gleneagles on climate change, not as long as Washington refuses even to recognize that a genuine problem exists.

"I just don't think the issue driving the agenda at the G-8 is science," he says. "A lot of these protocols are based on political will, not scientific knowledge. I don't think at this point that America is making its decisions on scientific facts."

As with AIDS and so many other scourges, it is the poor countries of this planet that will suffer most keenly if the world's leaders fail to make genuine progress on greenhouse gases — and quickly.

As an example of an extreme weather event, Piketh singles out the unprecedented rainfall and floods that inundated the southern African republic of Mozambique five years ago, causing widespread death and suffering. The country is still struggling to recover from the effects of that meteorological spasm.

"The developing world is not geared to deal with that," he says. "They don't have the reserve resources to fix things when they go wrong."

Nor do they have the political clout to make things go right.

The G-8 leaders who will gather at Gleneagles early next month may indeed possess that sort of clout.

The question is, will they use it?

G-8 Summit + Live 8 Concert = ''Media Circus''?

TheStar.com: 'G-8 Summit' - Search 2005-06-25 01:00:00 [Editorials]

Canada can afford to aid the poorest

Would Prime Minister Paul Martin plunge Canada into a fiscal crisis by doubling foreign aid, as Britain and others in the Group of Eight industrial club have pledged to do? Certainly, the raw numbers give pause.

...Given that number, Bob Geldof's blunt advice that Martin "stay at home" if he won't embrace 0.7 may sound churlish. The rock star/Live 8 promoter knows the United States, Japan and Russia are balking.

...But Canada is running a surplus, forecast to be $20 billion in the next five years. And we should get credit, too, for our military contributions to stability in places such as Afghanistan or Haiti. That is not always counted as aid.

So it is good to see Martin at least demanding that the finance department look into the feasibility of making that 0.7 per cent. That squares with his principled recognition that Canada has a moral "responsibility to protect" people threatened by tyranny, terror, poverty and disease. It also reflects his vision of Canada playing a "very ambitious" global role under his leadership, with a generous and better-focused aid program.

It is the logical extension of a Liberal agenda, launched by Jean Chrétien, to double foreign aid, to double aid to Africa, to forgive debt and to encourage poor countries to sell more goods here.

Rather than question whether our G-8 partners will live up to their pledges, as Goodale has been doing, Martin should recognize our moral duty, as a rich nation, to help the poor. Whatever our allies choose to do.

...Some Canadians would prefer to invest in health care and other domestic priorities. That's not an unreasonable point of view. But make no mistake: Aid is an investment in our own security.

...Martin has a choice at Gleneagles: He can reposition Canada in the forefront of major donor nations, or confirm us as a rich laggard. Only one of those choices can be called leadership.

2005-06-25 01:00:00 [World]The summit of love? TV movie a romance with a messageGirl in the Café could open some eyesCan a made-for-TV movie change the way people think about ending poverty in Africa?

The Girl in the Café director David Yates, who is also the man who will be behind the lens of the next Harry Potter film, is hoping the answer to that question is yes.

"If it affects one person," he said on his cellphone on the drive home in Oxfordshire, England, "it has made a difference...."

"We wanted to make a film that delivered that message to the audience in a slightly different way with characters that they could invest in and believe in. Hence this whole idea of making a film that's primarily a simple love story, which happens to take place in the middle of this big political summit."

Many of the facts stated throughout the film by can be found on the Make Poverty History website at http://www.makepovertyhistory.org

2005-06-21 01:00:00 [Editorials]

Pious G-8 waffle on global warming Tony Blair, this year's president of the Group of Eight industrial powers, looks once more to be stranded somewhere in the mid-Atlantic, this time over climate change.

Leaks of the draft plan on global warming for next month's G-8 summit at Gleneagles show it to have been holed below the (rising) waterline by U.S. objections.

Virtually all that was active in this action plan has been swept into the inert limbo of square brackets — meaning there is still no agreement on its inclusion — while much of what remains is pious waffle. His hopes for radical measures to combat climate change and determination to get George W. Bush on board seem to have collided. The summit simply has to do better than that.

Two weeks ago, the science academies of all G-8 nations, along with their counterparts in China, India and Brazil, stated unequivocally that global warming is a man-made phenomenon caused primarily by carbon-dioxide emissions. There was urgent need to attack the causes and prepare for the consequences of climate change. Yet the Bush administration insists too little is known about the phenomenon and the U.S. refuses to be bound by the Kyoto protocol on carbon emissions, which it believes would cripple American competitiveness.

The very least Gleneagles must deliver is a clear statement on the hardening scientific consensus. Instead, every reference to the observable impact of a warming world has been clamped by brackets.

Second, while political reality dictates that there will be a clear distinction between those who are in Kyoto and the U.S. which is not, Gleneagles must launch a structured debate on what happens after the emissions targets in the protocol lapse in 2012. As well as the G-8 this should include the leading developing countries.

Within that debate, America's insistence on technological innovation and cleaner fuels should come into its own, but there first has to be a common diagnosis of the problem.

It would be at best pointless, at worst positively damaging to proceed on the basis of this draft, which leaves wide open whether global warming is a fact or a hypothesis. The U.S. will not go the Kyoto route but nor will it fully mobilize its research and ingenuity around this problem until it recognizes it as a world-changing phenomenon that can no longer be ignored.

This is an edited version of an editorial from the Financial Times, London.Conservation still hard sell in China - TheStar.com

Jun. 30, 2005. 03:55 PMBooming economy taking a toll

Will be world's biggest polluter by 2020

IMAGE GETTY IMAGES FILE PHOTO

Cars sit in gridlock in heavy fog in Beijing. With pressure mounting for China to act on pollution, Beijing has pledged to cleanse the skies before the 2008 Olympic Games.

MARTIN REGG COHN

ASIA BUREAU

GUANGZHOU, China—Yang Ailun opens the venetian blinds on her ninth-floor office to reveal a curtain of yellowish-grey haze descending over the city skyline.

For the Greenpeace activist, the daily smog is a red flag. Two years ago her environmental group set out to paint Red China green, but a booming economy is pushing pollution into the stratosphere.

"Normally you can't even see the buildings right in front of us," Yang grumbles, peering at the clogged roadways and high-rises sprouting around her.

Second only to the United States in emitting the greenhouse gases that cause global warming, China is destined to become the world's biggest polluter within 15 years. Demand for coal-fired power plants that belch carbon dioxide fumes into the air is soaring faster than environmentalists like Yang can catch their breath.

Seven of the world's 10 most polluted cities are in China, where filth invades your eyes and coal dust clogs your throat. Yet here in the southern province of Guangdong, which bills itself as factory to the world, conservation is a hard sell.

Yang is one of 40 Greenpeace staffers campaigning to raise environmental consciousness across China, where economic growth is surging by nearly 9 per cent a year. Unlike flamboyant Greenpeace activists elsewhere, she can't organize publicity stunts or call public protests lest the Communist government shutter her offices.

"In China we're just at the beginning stages of raising public awareness," the young activist says diplomatically.

If China has been slow to wake up to the fallout from its factories, the rest of the world is watching closely — and holding its breath. Foreign environmentalists always buttonhole Yang at conferences to demand that China be more accountable for its pollution, but she says such attitudes will backfire.

"It's important for Westerners to understand that there are no moral grounds to just say, `Stop developing!'" Yang explains. "If you wag your finger and tell us how to run our lives, China will shut down the conversation and that would be the worst thing."

Yet the spotlight will be on China next week when President Hu Jintao sits in on the Group of 8 summit of industrialized nations from July 6 to 8 in Gleneagles, Scotland. With its superheated economy slated to quadruple in size by 2020 — and emissions of greenhouse gases likely to keep pace — Hu will be under pressure to do more to combat global warming.

China has ratified the Kyoto Protocol, which commits most industrialized countries to reduce greenhouse gases by 2012. But as a developing country, it is exempt from any commitments to curb pollution at home.

Moreover, Beijing has signalled it is in no hurry to accept any fresh obligations when the second phase of the treaty is due to take effect in seven years. Indeed, China is hedging its bets, waiting and watching to see whether the industrialized nations do more first.

"This is a very delicate question," Environment Minister Xie Zhenua told reporters earlier this month. "We still have time until 2012."

To date, China has vigorously opposed any voluntary or obligatory reductions by developing states. Increasingly, Beijing's negotiating position is that too much emphasis is being placed on reducing climate change — and that the world must learn to live with it — an unsettling stance for environmentalists.

Environmental stewardship has never been a priority in Communist China, whose Maoist ideology viewed nature as a force to be harnessed in the war on poverty. The environment was merely a battlefield, with pollution treated as collateral damage or welcomed as a sign of industrialization.

Political scientist Paul G. Harris, who specializes in China's environmental diplomacy, says Beijing strenuously resists any foreign lectures about curbing pollution, citing the West's profligate waste and cumulative harm to the environment. Nor will Chinese pride countenance any hectoring that smacks of the humiliations of its colonial past.

"It will set things back because the Chinese will dig in their heels," says Harris, who teaches at Hong Kong's Lingnan University. "You know how strongly China feels about criticism from the West, so it's very important that the G-8 says we (the West) accept responsibility for this problem and we have to act first."

Yet Harris cautions that China's indifference and defiance could backfire in the future, eroding its claim to leadership of the developing world. Global warming will disproportionately harm low-lying, flood-prone Asian countries like Bangladesh, which will one day ask why Beijing failed to heed warnings.

Despite its demands for disproportionate action from the West, China won't be able claim it was unaware of the dangers of its own pollution, which "raises very interesting ethical issues," Harris observes.

With the embrace of capitalism and the quest for prosperity, the country has shifted from Communism to consumerism. Now, the middle classes and even the masses aspire to have energy-guzzling electrical appliances at home. Government statistics show that China manufactures roughly 25 million refrigerators a year and twice that many air conditioners — with most destined for the domestic market.

"After all these years, everyone wants to enjoy the good life — luxury is a good thing to them," says Feng Wang, a volunteer with the environmental group Global Village of Beijing, which is trying to curb overuse of air conditioners.

China's mentality of "developing first and preventing and controlling pollution later" has been blasted as "absolutely wrong" by the country's most vocal environmental official, Pan Yue.

As deputy director of the State Environmental Protection Administration (SEPA), he warned this month that "the pollution load of China will quadruple in 2020" unless attitudes change and the economic trajectory eases up.

"Now we can see this 'workshop for the world' means that we, using our resources, produce low-level industrial products for developed countries and bear the harm of pollution," Pan argued in a speech.

China's industrial woes

SEPA made history last January by ordering 30 polluting major infrastructure projects, including 23 power stations, shut down because they had failed to secure environmental approvals. Yet by this month, all but one of the power stations had received the green light to resume construction, suggesting that SEPA lacks the clout to make other government departments go along — or even to enforce its will in the provinces where environment officials are beholden to their local political masters.

In prosperous Guangdong province, the local environment bureau is weighed down by an economy that grew by a staggering 14 per cent last year, placing extra strains on coal-fired power plants. Sulphur dioxide emissions jumped by 7 per cent and the number of vehicles on the road climbed by 12 per cent.

"Sometimes, under the pressure of economic growth, local leaders may not pay enough attention to this problem," vice-director Chen Guangrong says in an interview at his government office.

Guangdong is one of 10 provinces experimenting with the concept of "Green GDP" statistics so that the performance of bureaucrats will be judged on the overall impact of their policies rather than economic development at any cost. The program is in its infancy, but state media have reported that GDP would have been cut by 2 per cent if environmental costs had been considered.

"We're trying to deduct the environmental pollution loss from economic performance," says Chen.

Most funding for China's environmental programs comes from overseas donors, including more than $64 million from Canada since 2000, making it one of the biggest contributors.

Additional articles by Martin Regg CohnA continent's best hope - TheStar.com South Africa balks at AIDS medicine despite successes

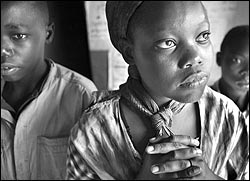

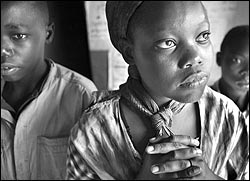

Limited access to anti-retrovirals `irresponsible' ANDREW STAWICKI/PHOTO SENSITIVE

ANDREW STAWICKI/PHOTO SENSITIVE

The AIDS scourge has left many families in Africa headed by orphaned children. In Tanzania, Helen, 17, is caring for brothers, Stanislaus, 15, and Edson, 12.  OAKLAND ROSS

OAKLAND ROSS

FEATURE WRITERSOWETO, South Africa—She is two years and four months old, her first name means "acceptance" in Zulu — and, if she were true to her name, she'd be dead by now.

Instead, Samakilisewe Mthimkhulu is a chubby little girl, bursting with life.

Barefoot, in a pair of hand-me-down red shorts and a red top, she wriggles on her mother's lap in the weathered little home they share along with five other children and a disease called AIDS, as the bronze winter sun drifts westward over Soweto.

In order to keep death at bay, Samakilisewe is obliged to swallow a spoonful each of three liquid potions every morning, potions that bear the outlandish labels of faraway pharmaceutical firms — Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline.

She does her duty without a fuss.

"She likes the medicine," insists her mother, Bongiwe, 32, who is HIV-positive herself, as are two more of her children. Only Samakilisewe so far has AIDS. "She even reminds me when it is time."

Unfortunately, not all South Africans are so diligent, starting with the health minister.

If she could, Samakilisewe would be perfectly justified in marching up to South Africa's minister of health and telling her to go take a flying leap into the nearest reservoir.

Health Minister Mzanto Tshabalala-Msimang, following the lead of President Thabo Mbeki, continues to cast doubt on the efficacy of a new generation of drugs known as ARVs, or anti-retrovirals — drugs that have saved countless lives in Europe and North America and that now offer hope to millions in Africa, when they are available.

In South Africa, for the most part, they are not.

"It's bizarre, it's irresponsible, it borders on the criminal," says Nathan Geffen, spokesman for the Treatment Action Centre, a South African agency that lobbies for greater access to these life-saving drugs. "There are a number of obstacles, but the one that stands in the way is the lack of political will."

The cavalier policies of the South African government constitute just one of the hurdles obstructing the provision of AIDS treatment in Africa, and they apply only to that country. For the rest of sub-Saharan Africa, governments are mostly willing but lack the means — the skilled personnel and the resources — to make treatment widely available.

A timely and generous response by wealthy donor nations might have gone a long distance toward alleviating the continent's plight — while saving millions of lives in the process — but that is not exactly what has happened.

"The level of delinquency on the part of the western world is astonishing," says Stephen Lewis, the U.N. envoy for AIDS in Africa. "I feel quite frantic about it."

As a result, in the part of the world that needs it most, ARV treatment has been late to begin, and distribution remains spotty and slow.

Meanwhile, people are dying — people whose lives could easily be saved.

Consider Samakilisewe Mthimkhulu, who as recently as this past March was gravely ill, thin as sticks, and drifting toward death — until she was put on ARVs.

Beginning on the eighth day of March, she rose again.

Since then, three white plastic bottles of medicine have made all the difference in the world to this one child in this one block of red-brick shelters located in this sprawling African suburb to the south of Johannesburg.

Samakilisewe is a very fortunate girl — one of the fortunate and the few.

Taken together, some 5.6 million of this republic's 44 million citizens are HIV-positive, possibly the largest concentration of such people in the world, challenged only by India.

Of these people, roughly 700,000 now are sufficiently compromised by AIDS that they require anti-retroviral treatment or they will surely perish, long before their times, just as thousands in this country — and more than 17 million people in all of Africa — have already done.

At present, however, only about 40,000 South Africans are receiving ARVs, a minuscule proportion of the sick and dying, and a rate of treatment that is far eclipsed by nearly all of this country's much poorer and far less developed neighbours.

Of all the problems that now confront this continent, none is more potentially catastrophic than this virus passed from blood to blood during sexual intercourse.

Only a few years ago, there was no hope of saving millions of people already infected with HIV, and instead African governments and international aid agencies threw most of their energies into trying to stop new infections from occurring, itself a wrenchingly difficult task.

Everyone now agrees that it is horrendously difficult to change people's behaviour — their cultural or sexual patterns — even when life and death are at stake.

"Behaviour change is the biggest challenge in prevention," says Derek von Wissell, head of the government anti-AIDS program in Swaziland. "I don't think anybody has cracked the nut of behaviour change."

Still, health authorities in a host of countries have done their best. They have issued dark warnings about the threat of AIDS. They have put on plays in schools, dramatizing the dangers of unprotected sex.

They have sent former commercial sex workers into African beer halls armed with condoms and wooden dildos, to demonstrate to hordes of inebriated men how the two go together.

They have promoted sexual abstinence and monogamy — and they still do.

Prevention of new infections remains the central strategy in the struggle against AIDS in Africa.

Yet millions of people continue to engage in unsafe sex, for many reasons.

- In many areas, condoms are simply not available.

- Besides, to people who are seriously hungry today, the potential consequences of HIV infection — death in eight or 10 years — might seem a somewhat distant and unreal prospect and therefore a poor disincentive.

- Finally, sex in Africa is not typically conducted between two equal and consenting adults. Women and girls are at a clear disadvantage both culturally and economically, and they rarely determine the terms of their relationships with men.

Here in South Africa, at least one organization has eschewed the sort of bleak, moralistic warnings that have long been the staple of AIDS-prevention campaigns on the continent.

"Our focus really is around positive lifestyles," says Scott Burnett, an official at LoveLife, a hip, upbeat AIDS-prevention agency in South Africa. "It's not about wearing condoms. It's about being positive about your future."

The agency's edgy slogan is "Get attitude."

"You, your future, your dreams," says Burnett. "That's our message."

Here's hoping it works.

In the meantime, however, people continue to contract and succumb to a disease whose ability to kill is proving even more formidable than the experts used to believe — and that is saying plenty.

"The early theories were that it couldn't hit 40 per cent," von Wissell says. "That is now thrown out the window."

In several southern African countries, including Botswana, Lesotho, and Swaziland, 40 per cent and more of the adult population have already been infected. Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe are not far behind.

If there were a cure for AIDS or a vaccination against the disease, then almost everything would change. But, so far, there is neither.

For Africa, for now, the best hope resides in just three bottles of pills, multiplied over and over again — the standard, triple-drug regimen of anti-retrovirals that is already saving and enhancing tens of thousands of lives on the continent.

Unless you happen to be the South African minister of health, the effectiveness of these medicines is impossible to deny.

Tshabalala-Msimang would be well advised to pay a visit to Cotlands, an AIDS orphanage located in Turffontein in the south end of Johannesburg, where there are always at least 60 youngsters prancing about the brightly lit corridors or resting in the dormitories, with their Shrek 2 bedspreads and stuffed animals.

"I'm a firm believer in anti- retroviral treatment," says Allison Gallo, who works at the orphanage. "I've seen the condition of our kids improve dramatically."

The orphanage's facilities include an 18-bed hospice, where staff workers provide palliative care for seriously ill children, some of whom are in the final stages of AIDS. A few youngsters, unable to breathe on their own, are hooked up to oxygen tanks. Others are excruciatingly thin — the epitome of starving babies.

Prior to the introduction of ARV treatment at Cotlands, the orphanage was losing children to AIDS at the rate of three or four a week, says Gallo. There was nothing to do but care for them until they died.

What a difference a few drugs make.

So far this year, only five children at the orphanage have died of AIDS, a nearly miraculous turnaround.

"Many children come in looking really dreadful, and we don't think there's much hope," says Gallo. "But, after a few weeks, there's a tremendous difference."

In many poor African countries, the will exists to provide treatment for AIDS, but there is a woeful lack of "capacity" — physical and organizational resources and skilled people to make use of them.

In Malawi, for example, there are just 350 or so doctors in a population of about 12 million people. Only two of those doctors are pediatricians.

In Swaziland, ARVs are available at only five government hospitals, where they are provided free of charge. But that's not much help if you live in the country's eastern lowlands, where the nearest government hospital is in Manzini, a four-hour bus ride away. The journey costs 20 emalangeni, equivalent to about $3.65 (Canadian) or 15 per cent of the average rural-dweller's monthly income.

And so people die.

But the dead do not include Nokhwezi Hoboyi, even if she has lost two newborn children to AIDS.

The young Cape Town woman was infected with HIV in 1998, but her doctor refused to tell her so. She lost her first baby, then another, and finally became very ill herself.

By 2002, she was passing out at work, and it was only then she found out that she had AIDS and she was dying. She would have died, too, were it not for ARVs. Now she takes two pills in the morning, three at night.

"A lot of people have died without being able to access treatment," she says. "They have died without knowing their options."

And, by the tens of thousands, Africans continue to die — deprived of the medicine that surely could save them.

"I have improved," says Hoboyi who, at age 25, has a long life ahead of her. "I feel very much great."

But she is one of the fortunate — the fortunate and the few.

Swaziland: A land of AIDS and orphans - TheStar.com

Jun. 26, 2005. 08:44 AM

NCEKA,SWAZILAND

Swaziland: A tiny African kingdom tries to tackle the Goliath of epidemics.

Swaziland: A tiny African kingdom tries to tackle the Goliath of epidemics.

Mfan'fikile Dlamini is starting over.

At the ripe old age of 16, the orphaned former herdboy and former abused child is going to school for the first time in his life.

He says he is happy, too — and that's probably another first.

"Yes, I am," he says in his native Swati, a southern African click language closely related to Zulu. His head bobs nervously as he speaks and he fidgets with the pages of a Grade 1 workbook. "I am now able to read."

The newly literate youth is hunched in the cool shade of a rural schoolyard, flanked by several of his much smaller classmates, all of whom are about a decade younger than their lanky new friend, a disparity that no one seems to mind. They all have illustrated workbooks balanced on their laps and are practising their morning lessons.

You can readily imagine how difficult it must have been for Mfan'fikile to summon the courage to come to school for the first time, starting back at the beginning, surrounded by children less than half his age.

But that is what he has done.

"He had been looking after cattle for all these years," says Maria Sikhondze, headmistress at the Sinceni Mission Primary School. "He was afraid of coming to school, because of the age difference."

The age difference is just one of the many hurdles that Mfan'fikile has had to overcome in his short life. But here he is, very much alive, with a schoolbook in hand, friends at his sides and a view that stretches out over the eastern low veldt of the kingdom of Swaziland, a vista composed of a parched expanse of communal grazing lands decorated with acacia trees and bordered to the west by the proud Hhohlo hills. It's a handsome prospect in many ways, or it would be, were it not for one thing.

The kingdom of Swaziland is increasingly a kingdom of death.

This little monarchy of 1 million souls, bordered by South Africa and Mozambique and ruled by His Highness King Mswati III, holds the dismal honour of having the world's highest infection rate of HIV, a complex and so far intractable malady that many people here are reluctant to talk about, even as it stalks them down and lays them low, like so many antelope on the run.

Currently, nearly 43 per cent of adult Swazis are HIV-positive or have AIDS, a disease that killed 20,000 people here last year, will kill another 20,000 this year and a similar number next year, and so on, into a dimly perceived future.

The outlook is not much better in many other parts of Africa.

There are those who worry that this kingdom, like several other southern African lands — Lesotho, Malawi, perhaps Zambia — is in danger of complete collapse. Its adult population gutted by AIDS, the long-time home of the Swazis may eventually cease to exist as an independent nation.

And yet, if Mfan'fikile can survive all that he has so far endured — and not lose hope and still be willing to start again from scratch — then you must believe that Africa can do the same.

But the task will not be easy, for the hour is late and the outside world has been unconscionably slow in coming to the aid of this country and this continent.

The world's next chance early next month, when the leaders of the G-8 nations — Britain, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia and the United States — grapple with Africa's AIDS crisis as one of the cornerstones of their summit meeting in Scotland.

"On the ground, when you travel, it is still despairing and overwhelming," says Stephen Lewis, the Canadian who serves as the United Nations special envoy for HIV/AIDS in Africa. "I've come to the point where the saving of one human life is what's it all about."

Mfan'fikile Dlamini is one human life.

An apparently guileless youth, with a handsome oval face and dark, liquid eyes, he wears a white polo shirt, black track pants and running shoes — clothing given him by an international aid agency. Like many other students here, he cannot afford the green-and-gold uniform of the Sinceni school.

Anything that costs money, Mfan'fikile cannot afford. Not many people around here can.

The numbers don't do justice to the reality, but here are the numbers. Fully 70 per cent of Swaziland's people subsist on the equivalent of $1 a day, many of them on a lot less.

"Their annual income is barely enough to buy a coffin if they die," says Abdoulaye Balde, the country director for the World Food Program, which is desperately trying to provide emergency food to 250,000 hungry Swazis, a quarter of the total population. "It's nothing."

Balde is speaking of the country as a whole, but the kingdom's eastern lowlands are impoverished even by Swazi standards. What's worse, this year the region suffered its fifth straight season of meagre rainfall. Even without the predations of AIDS, times would be tough.

As it is, they are harrowing.

"Parents, left and right, have died," says Sikhondze, an imposing, matriarchal woman of 57, clad in a round-brimmed blue hat, long black jacket and blue dress.

She hobbles about the sloping grounds of her school like an angel in mourning.

"Some students are staying alone in their homes. Families are headed by these kids."

These kids are the offspring of AIDS.

You cannot always see it, but the disease is everywhere in this land. It's on people's minds. It's interred in the ground. It lurks in the blood.

It shows up constantly in the pages of the kingdom's two newspapers, The Times and The Observer, whose classified columns brim daily with dozens of death notices — picture after picture of mostly young adults who have slipped away, long before their time, the cause of their passing never mentioned in print.

HIV pervades much of sub-Saharan Africa, but it's sometimes strangely difficult to detect, perhaps nowhere more so than in this small kingdom, ruled by a hereditary monarch with 10 wives, a royal palace and a personal jet.

The two main Swazi cities — towns, really — are the capital Mbabane and Manzini, about 25 kilometres to its southeast. Both are busy little centres, infused with an air of purpose and bustle. They are connected by a four-lane, illuminated highway that puts the Macdonald-Cartier Freeway to shame.

The mountain scenery is stunning. You cannot see the dead.

But here in this dry, rocky savannah land, anyone can perceive at a glance what death has wrought. It has wrought emptiness — a near absence of adults — and it has wrought orphans.

"We estimate 70,000 orphans now," says Derek von Wissell, a white-skinned Swazi who is in charge of the National Emergency Response Council for HIV/AIDS, a government-controlled agency.

"This will grow to 120,000 orphans by 2010."

That's about 12 per cent of the population — or one person in eight.

Amid Swaziland's onslaught of woe,

experts are at last starting to glean still-

tentative signs that something may be

changing for the good in the tiny kingdom

No one really knows what to do about this tide of parentless children. An American evangelical pastor by the name of Bruce Wilkinson has offered to take over a couple of the kingdom's wildlife reserves to build huge orphanages that would be financed by the operation of tourist theme parks — Disneyland meets the Apocalypse.

But few here seem receptive to the idea.

Right now, both the Swazi government and international agencies such as UNICEF are determined to address the country's swelling ranks of orphans by keeping the children close to their communities.

Authorities have set up more than 400 posts around the country — known as neighbourhood care points, or NCPs — where orphaned, abandoned or hungry children may come for food or other kinds of support.

The World Food Program and various partner agencies distribute the food, while local adults — those who remain — act as unpaid caregivers, feeding and tending to the hapless youngsters for six hours each day.

The caretakers are a hardy but put-upon breed.

Thuli Dlamini, for example, is standing in the sparse shade of an umkhuhlu tree at a village called Dziya, not far from the Sinceni school. She is tending a wood fire and three steaming cast-iron pots, in which she is preparing a hot lunch for 44 young children, all of whom are being cared for at the local NCP.

The meal will consist of bean stew and a corn porridge known here as papa, the country's staple food.

(A great many Swazis, including the king, bear the surname Dlamini. Generally, they are not related to one another or only distantly.)

Forty-two years old and with six children of her own, Thuli has also taken in five nieces and nephews, who became orphans when her brother and his wife died not long ago — she won't say of what. She is expecting to receive six more children soon, from an ailing sister.

Her own husband works as a labourer in the sugarcane fields near a town called Big Bend, coming home only on weekends. He is unwell, too. Thuli says it's high blood pressure, and maybe she is right.

A few steps from Thuli's cooking fire, the children of the Dziya NCP are learning the rudiments of English from another caregiver, Nonhianhia Shabangu. "We are standing up!" they cry, bouncing on their small feet. "We are standing up!"

A Norman Rockwell canvas, it is not. But at least these children have food to eat and, for the most part, they appear healthy. As matters stand, however, only about 30,000 Swazi children have access to an NCP, leaving at least 40,000 orphans and tens of thousands of other vulnerable children without outside help.

"We have at least 150,000 kids who are not getting the most basic support they require," says Alan Brody, head of the UNICEF office in Mbabane.

"They are invisible."

They are also open to sometimes-shocking abuse.

"Older men are basically preying on younger girls," says Anurita Bains, who works with AIDS envoy Lewis.

It's called "survival sex" and it is the only way many children can find to put another day between themselves and the grave, trading their bodies for some food, a few coins, anything to get by.

Often, the children receive an unmentioned dividend in the bargain, a deadly dose of HIV.

The sexual exploitation of vulnerable children is not merely a loathsome footnote to the story of AIDS in many parts of Africa, it is also an increasingly powerful vector for the spread of the disease from one generation to the next.

"This is the fire that is burning," says Brody at UNICEF. "It is a big problem."

Unfortunately, it gets worse. In Swaziland, as elsewhere in southern Africa, some adult males believe they can rid themselves of AIDS by sleeping with a virgin. Vile as it may be, the superstition persists — with horrific consequences.

"I don't have another good explanation for why we have men raping very, very young girls," says Brody.

For orphans in Swaziland, the misery of sexual abuse is compounded by another grim fact of life in the time of AIDS. There is generally nowhere for them to go for comfort or counsel, because the favourite aunts or uncles of happier days are now likely to be dead.

In Swaziland, authorities are trying to compensate for this breakdown in traditional kinship structures with a program called Lihlombe Lekukhalela, Swati for "A Shoulder to Cry On." The goal of the campaign is to seek out responsible, caring adults and identify them as people to whom troubled children may go for advice, solace, a heartfelt embrace — commodities that are all in short, but desperately needed, supply.

Amid this onslaught of woe, experts here are at last starting to glean the hazy and still-tentative signs that something may finally be changing for the good in the kingdom of death. Among Swazis ages 15 to 19, the HIV prevalence rate eased downward last year to 28 per cent from 34 per cent in 2002.

"It could be a glitch in the figures," says von Wissell. "Or maybe there's something happening in this group."

Either they are using condoms or they are abstaining from sex or they are limiting their sexual partners — or all three.

If the figures are accurate, this is the first heartening news in a long, dark time.

As matters stand, more than 200,000 Swazis, or nearly one-quarter of the total population, are reckoned to be HIV-positive. Of these, about 25,000 are sufficiently ill to require anti-retroviral medication — drugs capable of keeping people with AIDS alive and mostly healthy. ARVs are provided free here, but distribution is a problem.

Only about 10,000 Swazis are receiving the drugs, between one-half and one-third of those who need them. Still, this is a far better rate than Swaziland's much larger and wealthier neighbour, South Africa, has achieved.

In fact, some here believe that this little kingdom, despite its many sorrows, could yet provide an example in the fight against AIDS in Africa.

True, the king receives a lot of bad press, thanks to his extravagant tastes in wives and imported consumer goods, but in fact the government here is openly committed to the fight against the disease and has committed considerable resources to the struggle.

"Make this an experiment," says Balde at the World Food Program. "I believe Swaziland is so small a country that, if you don't get it right here, let's not even think about it elsewhere."

Much has already been lost to AIDS in the kingdom of Swaziland and much more inevitably will be wrested away, including nearly all the economic and social gains achieved during 37 years of independence. Still, when the disease has finally done its worst — and no one knows when that will be — Swazis will have no choice but to start over again, from scratch, just like their counterparts in many other African lands.

Some of them already are.

Consider Mfan'fikile Dlamini, a boy denied schooling because his parents couldn't afford the fees. All his young life so far, he has tended cattle — at least until his mother and father died, cause of death unknown. Mfan'fikile was sent to live with an aunt, but she beat him so regularly and severely that finally he ran away.

That was last year, when teachers at the Sinceni school found the youngster wandering aimlessly through the nearby hills, dressed in rags. Since then, his life has been transformed.

A local resident has taken him in, he has decent clothing and now the 16-year-old is a student for the first time in his life, his fees paid by UNICEF.

It took a little help, but Mfan'fikile is starting over. If he can do it, maybe Africa can.

India's deadly secret: HIV/AIDS explosion - TheStar.com

Virus has begun long-feared breakout

Spreading uncontrolled among 1 billion

ROBERT HOLMES/CORBIS

Prostitutes line Falkland Rd. in Mumbai, India. Their customers are rapidly spreading HIV/AIDS from the red-light districts of India’s big cities to the hinterland.

MARTIN REGG COHN, ASIA BUREAU

MUMBAI—Setting off on her daily rounds, Alka Gaikwad heads through the city's labyrinth of slums to an unmarked home.

Inside the gloom, Bharti Dhamankar hunches over a makeshift shrine of fresh garlands draped over a faded portrait of a ruggedly handsome young man.

For five years, the man in the photograph lived with HIV/AIDS. Two weeks ago, he died of it. Along the way, the former truck driver infected his wife.

Now, his 31-year-old widow can think only of the medical death sentence facing her — and the destiny of her two young children who will become orphans. Choking on grief, she is unable to speak.

And so Gaikwad, in a bright floral print sari, steps into the silence. The volunteer counsellor goes on house calls well prepared, for she, too, is an HIV-positive widow — infected by her late husband a decade ago.

Gaikwad, 33, witnessed her daughter's death from the virus a few years later. But the survival of her teenage son has inspired her to keep living, and counselling.

"I want my son to grow up and stand on his own feet," she says. "Until then, I won't die."

Recruited by the foreign development charity World Vision, she comes face to face every day with what most Indians never see — and the world barely acknowledges: The uncontrolled spread of HIV/AIDS in a country of 1 billion people.

Since its arrival among prostitutes in the southeastern port city of Chennai nearly two decades ago, the virus has begun its long feared "breakout" — spreading from high-risk groups to the general population. Legions of truckers and millions of migrant workers are spreading HIV/AIDS from the red-light districts of India's big cities to women in the hinterlands.

More than 5 million Indians are infected with AIDS or HIV (the virus which causes AIDS) according to rough government estimates. Officially, the United Nations ranks India as the second-biggest hotspot on Earth, slightly behind South Africa's 5.3 million infected people.

But while the world's attention remains focused on Africa, many analysts and health workers think India is incubating a greater AIDS disaster of global proportions. The 5 million figure is too conservative, they say.

"The official statistics are wrong — India is in first place," warns Richard Feachem, respected executive director of the Paris-based Global Fund to Fight AIDS, set up in 2001 by the G-8 group of industrialized countries. India "is or is becoming the global epicentre for the pandemic."

By 2000, an estimated 2.8 million Indians had died of AIDS, and the U.N. projects another 12.3 million deaths by 2015. The U.S. National Intelligence Council has warned that 25 million Indians could be HIV-positive by 2010.

Yet, when the G-8 leaders grapple with Africa's AIDS crisis at their annual summit next week, India's hidden epidemic won't be high on the agenda. Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh is attending the summit in recognition of his country's emergence as a diplomatic power — but the talk will be of economic growth, not India's AIDS earthquake.

In fact, India's outbreak is at a critical stage, offering a historic window of opportunity to control the spread of the virus. If AIDS makes further inroads here, the consequences for the world will be enormous — with India ultimately overtaking all of Africa in the number of HIV-positive people.

Government data suggest an infection rate of 0.9 per cent — far less than the 21.5 per cent prevalence of South Africa, to be sure. But the nationwide figures mask a series of alarming regional epidemics of up to 5 per cent in some of India's southern states, where testing facilities and hospitals are more reliable.

"The more relevant figure is the trajectory of the epidemic, and we see a very steep trajectory," says Ashok Alexander, head of Avahan, the anti-AIDS group established in India by the Gates Foundation. "It's different from the African epidemic — we're going to see big explosions in clusters."

The result could be social and economic upheaval, yet "India is not even on the radar screen of the international community as far as HIV/AIDS, and that's a tragedy as far as I'm concerned," Ashok argues. "I think it will get worse before it gets better."

If the numbers are indeed understated in the rest of India, an AIDS disaster is in the making not only here but, eventually, everywhere. Every 1 percentage point increase translates to another 5 million infected people.

"We think it's much higher, obviously, than what the government is saying," says Anjali Gopalan, head of the non-profit Naz Foundation, which runs a home for AIDS orphans and HIV-positive mothers in New Delhi. "We have lost that window of opportunity."

As India braces for battle against AIDS, it is beset by familiar handicaps: endemic poverty, cash-starved health care, deep-rooted public prejudice and official neglect.

HIV-positive people are India's new untouchables.

Against that backdrop, India has one clear indigenous advantage: a world-class pharmaceuticals industry that produces high-quality anti-AIDS drugs known as anti-retroviral therapy (ARV).

But that head start has been squandered. Due to remarkable government foot-dragging, Indian-manufactured drugs are more widely available overseas than on the streets of Mumbai.

Of the 5 million Indians officially estimated to be HIV-positive, a mere 7,500 — including Gaikwad — are getting free ARV medicine, and another 23,000 are estimated to be obtaining it privately. That's less than 1 per cent of those in need.

In Gaikwad's case, the discovery that her daughter was HIV-positive brought discrimination and humiliation. A hospital doctor refused to treat the girl — an all too frequent reaction that sets a negative example for the general public.

"The medical profession in India has been at the root of much stigmatization and discrimination," says Alexander.

Fear of catching AIDS turns even family members against one another in a manner reminiscent of historical caste prejudices.

"Within my own family, we are treated as untouchables," says Chaya Jamadade, 30, another widow seeking help from Gaikwad. "We cannot touch the food, dinner plates or soap."

After she was widowed and found to be HIV-positive, family members ordered Jamadade's children to keep away and tried starving her to death. They withheld food for nine days, she says, until police intervened.

"They thought I would just die off or go live elsewhere. They kicked me out. They used to beat me until I couldn't bear it any more."

Gaikwad stepped in to help, bringing only an infectious smile into the household.

"I visited the house, talked to the family and neighbours about how HIV doesn't spread so easily," she recalls.

But the AIDS scare dies hard. A report by New York-based Human Rights Watch last year documented widespread discrimination against infected children and orphans in the classroom, hospitals and their own homes.

"You see people kicked out of their homes, and this I have not seen even in Africa," says Dr. Denis Broun, who heads the U.N.'s AIDS operations in India. "This is something that AIDS has done to India."

Irrational fears of AIDS transmission and taboos about sex have set back India's efforts to raise public awareness and detection. People who suspect they might be HIV-positive go underground, refusing even to be tested for the virus. That reticence has lethal consequences for HIV-positive people.

Without testing, people don't seek treatment; without widely available treatment, people have little incentive to be tested — they consider a positive result a death sentence.

"India is very much behind in terms of access to treatment," says Broun of UNAIDS.

"At least 500,000 people should be getting it."

The fact that ARV drugs are manufactured cheaply in India yet remain inaccessible to so many Indians exasperates Yusuf Hamied. As head of Cipla Ltd., which makes low-cost generic drugs, he has spent years trying to shame the Indian government into distributing medicines that could prolong lives.

At first, he encountered bureaucratic indifference — a feeling that India had to marshal its scarce resources for cost-effective prevention rather than costly treatment. He countered by slashing prices and offering free pills, but officials stubbornly refused to lower tariff barriers on his imported ingredients.

Belatedly, the government is funding a program to place 100,000 people on ARV by 2007, yet only a fraction of that target has been reached. Now that the government has mustered the political will, finding a practical way is proving difficult.

Across town from Cipla's sleek offices and modern production facilities, Mumbai's seedy brothels do a booming business. Women in heavy makeup line Falkland Rd. day and night, tempting new customers.

With her faded red nail polish, nose stud and long black hair, Shila Ramagauda pays close attention to her appearance — and her health. To maintain her earning power — about 100 rupees, or $3 a client — she starts her workday by packing both cosmetics and condoms.

"I know how to protect myself, but I'm still a little bit scared," says Ramagauda, 25.

With a 5-year-old daughter to support, she can't afford to die on the job. She counts on condoms for survival, gently persuading customers to co-operate.

"We are very clear about it. We tell them: `You have a family; this is not only for you, but also you have to protect your loved ones.' So this helps us deal with their anger."

What if customers claim to be unmarried?

"We tell them, 'You may be young, but you will want to start a family one day, and you'll put them at risk without a condom.'"

If a client still refuses a condom, she puts one on herself — resorting to the alternative female condoms sold at subsidized prices by aid groups such as Population Services International. The female condom has more lubrication than standard male condoms, so in the darkness of brothels and the haze of alcohol, customers are often oblivious to their use.

After a slow start, there is optimism that a change in government last year has brought a shift in India's approach to AIDS.

The previous Hindu fundamentalist government nixed condom ads on TV, but Singh's new Congress-led government is not so squeamish.

The prime minister has given his blessing to a more provocative — and effective — marketing strategy led by the National AIDS Control Organization and promised to double its budget.

Now, NACO director S.Y. Quraishi is trying to kick-start the mammoth Indian bureaucracy.

Quraishi is determined to change the way Indians think about safe sex. His model is the multinational soft-drink giants that persuaded villagers to start drinking bottles of sugared, carbonated water.

"If everyone can be tempted to drink Pepsi, why not condoms, surely?" he asks, pointing to prophylactic condom packets and posters distributed by his office.

"Information is the only vaccine we have, so we have to catch young people before AIDS catches them."

Strange sights in the Arctic light - TheStar.com

In the Arctic, the signals are loud and clear. But is anyone listening?

Songbirds are heard trilling in the Yukon like never before

But it's not good news: Climate change is hurting the North

TANNIS TOOHEY/TORONTO STAR

Abraham Klengenberg hangs fish to dry as his grandsons play by the Arctic Ocean. Global warming caused the winter’s ice to melt this year three weeks sooner than normal.  Jun. 29, 2005. 07:49 AM

Jun. 29, 2005. 07:49 AM

PETER GORRIE

FEATURE WRITER

TUKTOYAKTUK, N.W.T.—On an intensely bright late-spring day, Abraham Klengenberg descends the short slope to the gravel beach, pushes his red canoe into the placid Arctic Ocean and paddles out to tend his fishing net.

Klengenberg, a 54-year-old Western Arctic Inuk, doesn't go far. The ice has just receded from this part of the sea. As it went out, it stirred the bottom sediments, turning the frigid near-shore water into a banquet table for fish.

An hour after the net is set, its marker buoys are under water, signalling it's heavy with five- to eight-kilogram whitefish and inconnu.

Soon, the catch is cleaned, split and hung over a simple drying rack. Later, it will be smoked.

Klengenberg — a wiry, weathered soft-spoken man — grew up in Tuktoyaktuk. His routine, like the sea's bounty, seems timeless and unchanging.

Except that now, to get to and from the beach, he must pick his way around and over large, angular chunks of stone known as riprap.

They were trucked in over the winter ice road from a quarry near Inuvik, about 100 kilometres to the southwest, at a cost of $600 to $1,000 a load.

Riprap now covers most of the shoreline of this ragged, dusty hamlet, a motley collection of houses, whose winter-blasted paint matches the greys and browns of treeless streets and yards. It's there to keep the land from being washed away as the sea level rises and storms hit with increasing ferocity.

Tuktoyaktuk housed one of the DEW Line radar sites installed in the 1950s to warn North America of aerial attacks from the Soviet Union. Its rows of jagged rock are an alarm signal for what most scientists insist is a far greater threat — climate change.

Carbon dioxide, methane and other "greenhouse" gases, produced mainly when humans burn fossil fuels such as oil and gas, are building up in Earth's atmosphere. Just like the glass in a greenhouse, they prevent the sun's heat from bouncing back into space.

The result is often called global warming, because Earth's average temperature is rising. Scientists prefer climate change, since the potential impacts go far beyond hotter summers and mild winters

It is, along with poverty in Africa, to dominate the agenda for next week's annual G-8 summit, July 6-8, where the leaders of Canada and seven other industrial nations are to meet at posh Gleneagles, Scotland.

Indications are the summit will generate little action on climate change. Although its host, British Prime Minister Tony Blair, has called it "probably, long-term, the single most important issue we face as a global community," the United States continues to reject targets and timetables for reducing emissions, and still insists there's no serious threat.

Few people in Tuktoyaktuk will be glued to their TV sets for summit coverage, but all of them know what they see outside their homes.

It's not just the rising water and more frequent storms. The ice breaks weeks earlier, and much faster, than it used to in spring, and forms more slowly each fall. The weather is less predictable. These are hazards for the many residents who still go out on the land to hunt seal, polar bears, muskox and caribou. The wind blows from the south more often. Long-time residents see grizzly bears, ravens, white-throated sparrows, chickadees and other creatures that never used to venture this far north. Shrubs are poking up beyond the tree line. Permafrost is starting to melt.

Tuktoyaktuk means, in the western Arctic language, "resembling a caribou." The animals are a major food source. The longer growing season produces more vegetation for them to eat. But the early thaw slows their trip to summer calving grounds on the Arctic coast, and calves born during migration are less likely to survive. Local researchers say one of the two local herds, the Porcupine, has dropped by 3 per cent a year for the past decade.

Klengenberg — like many people here a mix of Inuk and Caucasian blood — says he's not worried by the changes: "I just take it as it comes."

"Even Eskimos welcome the warmer summers," jokes his friend Charles Angun, 59, another lifelong resident who has gathered evidence that the sea ice is, on average, thinning.

Others in Tuk are less sanguine.

Jackie Jacobson, the 32-year-old mayor, points to a shoal that's barely visible in the water, 30 metres off the narrow, curved gravel spit that shelters the harbour. "When I was a kid, we would walk out to where the sand is," he says.

The spit itself is a small fraction of its former width and height. In a recent storm, waves crashed over it and across the harbour. "It's something when there's a storm and you see three- to four-foot rollers coming into the community," says Jacobson, big in size, energy and generosity, and wearing the North's trademark jeans, windbreaker and baseball cap.

He has pleaded with the cash-strapped Northwest Territories government for more riprap. He's received sympathy, but no rocks.

All this started happening 10 years ago, he says. "Scientists came up and said global warming is happening. Now you see the effects on the community."

In fact, signs are being noted around the world.

Researchers acknowledge they have no absolute proof: They talk, instead, about the balance of probabilities.

They know the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere has increased by more than 30 per cent since the start of the industrial revolution 200 years ago, and could double by 2050. They have devised massive computer programs to simulate and predict what the buildup might lead to. And they do tests in the real world — almost every one of which confirms the forecasts.

A few skeptics say Earth is just going through a natural cycle. The vast majority, though, are certain what's happening is the result of human activity and that it could make much of the planet uninhabitable — at least, for people.

Some evidence, like the impact on Tuk, is anecdotal.

The weather is more severe: drought in Europe and southern Africa, lethal floods in China, and devastating hurricanes in Florida. Canada has experienced a destructive ice storm, record snow and rain in the east, and tinder-dry B.C. forests bursting into flame. In southern Ontario, heat-induced smog arrives earlier and more often.

Cougars and magpies are being spotted for the first time in the southern Northwest Territories. Previously unseen songbirds trill in the Yukon.

Other signs seem more clearly tied to rising temperatures.

Climate change is 'probably, long-term, the single most important issue we face as a global community'

- Tony Blair, Britain's prime minister

Increasing areas of the Arctic ice cap melt each summer, and the remaining ice is weaker.

In Alaska, buildings are sinking as permafrost melts.

Everywhere, glaciers are retreating. A study of 244 Antarctic glaciers found that 87 per cent have shrunk over the past 50 years. The Greenland ice sheet that spawns icebergs is sliding increasingly fast toward the sea on a new layer of melt-water.

Some of the most convincing evidence comes from complex scientific tests that measure tiny increments of change.

- Earth's temperature is rising. In the 20th century, the global average increased by about 0.6 degrees. The Arctic rose one degree. The warmest years have occurred in the past decade.

- The oceans have warmed by about half a degree in the past 40 years. Scientists say that's proof Earth now retains more energy from the sun than it emits into space. Some call this the "smoking gun" of climate change.

- Sea level has risen one to two millimetres a year since 1900. The average annual increase over the past 3,000 years was one-tenth as much.

- Subtle changes in temperature and salinity in the North Atlantic Ocean fit with predictions climate change will stop the northward flow of warm water that gives Britain and Europe their moderate climate. A British scientist this year found no sign of six of the eight columns of rising water that fuel the current. The eventual result might be an end to

Europe's heat waves and colder weather. - University of Alberta scientists have found increased diversity of microscopic plants and insects in the North, thanks mainly to a longer growing and ice-free season.

Some consequences are easy to forecast. The Arctic and Antarctic ice caps will keep melting. Because of that, and since water expands as it warms, sea levels will continue to rise, flooding coastlines and inundating low-lying islands.

But most potential impacts are complicated and, to some extent, unpredictable. Earth is governed by massive forces that work in a delicate balance: If one part of the system changes, everything does.

"We don't have any experience to guide us in determining what will happen to a system this big and complex when you hit it this hard," says Ralph Torrie, a long-time energy and environment analyst who is now a vice-president at ICF Consulting Group Inc., in Toronto. "We are the experiment."

Initial changes could lead to others.

Severe drought, interrupted by the occasional intense storm, is forecast for the Great Lakes region. The hotter weather would increase evaporation, which would not only lower the lakes' levels but also add moisture to the air. That could lead to more violent storms.

The pace of change is also the subject of debate, partly because some impacts will feed upon themselves in ways that make calculations difficult.

A great deal of plant material is locked in the North's permafrost. If the frozen ground thaws, that material will decompose, sending huge amounts of methane — among the most potent of the greenhouse gases — into the air.

Bright white Arctic ice is an extremely reflective surface. As it melts, it will be replaced by open water, which absorbs heat. So even more of the sun's energy will be retained than the increase in greenhouse gases would anticipate.

On top of that, the gases stay in the atmosphere, and the oceans retain the excess heat, for decades. Even if emissions stopped completely, climate change would continue.

But they won't stop.

The Kyoto Protocol, which calls for developed countries to cut their emissions by roughly 6 per cent below 1990 levels by 2012, is only a modest step that might slow climate change slightly. Even so, of the countries that signed on, only a few in Europe are on target.

Canada's emissions have risen by about 20 per cent. Even worse, after several years when they increased slower than economic growth — indicating, at least, that we were getting more efficient — in 2003 they rose nearly twice as fast as the gross domestic product.

The United States, the world's biggest polluter by far, pulled out of the Kyoto agreement after George W. Bush was elected president. Most forecasts assume U.S. emissions will double during the next century.